Recent research has led to a clearer understanding of how life loads (gravity and low and high loads of function) are transferred through the thorax (chest), low back and pelvis/hips and from this research it is evident that low back pain and stress urinary incontinence have components in common. A multi-centered study in Holland investigated how common a combination of the two conditions (low back pain and stress urinary incontinence) was. In a study of 66 patients, 52% reported a combination of low back pain along with some form of pelvic floor dysfunction (voiding dysfunction, urinary incontinence, sexual dysfunction and/or constipation). Of these 52%, 82% stated that their symptoms began with either low back or pelvic girdle pain.

We now recognize that the factors which must be optimal for a healthy low back and pelvis and those that must be present for urinary continence are often the same. The goal of restoring a healthy low back and pelvis is to ensure movement patterns are trained that optimize the transference of loads through all the joints and organs. The result is motion control AND mobility, where there is controlled joint motion without rigidity (bracing), without episodes of collapse, and with fluidity of movement. In addition, the strategy used should not cause excessive intra-abdominal pressure on the organs of the pelvis (bladder, prostate, uterus etc.)

Your therapist at Diane Lee & Associates will give you a very thorough examination of the joints and muscles of your low back and pelvis as well as an assessment using ultrasound imaging to see what strategy you are using to manage loads through your pelvis. An individual treatment program will be developed that is specific to your needs. Hopefully, you will learn to support the organs of your pelvis and keep them for a lifetime avoiding what we believe is NOT inevitable with time – stress urinary incontinence.

The low back and pelvic girdle

The ability to effectively transfer load through the low back and pelvis is dynamic and depends on:

- optimal function of the bones, joints and ligaments

- optimal function of the muscles and fascia

- appropriate function of the brain and nervous system (which controls your muscle system and can be affected by many things including your emotional state).

There is a small amount of motion between the joints of the pelvis, and this motion needs to be controlled in situations that put load through the low back and pelvis (sitting, standing, walking, running, etc.). Motion control is provided by the contraction of certain muscles at the right time and the right place, as well as by ligaments that are intact and the right length. We now know from research that certain muscles should contract to prepare the bones and joints for loading before other muscles contract to create the movement. Optimal function therefore requires proper coordination of your muscle system – with the right muscles turning on at the right time, with the right amount of force. This is not only about strong muscles – it is about your brain and nervous system being able to orchestrate proper patterns between the muscles to create beautiful movement.

Research has shown that, in health, when the central nervous system can predict the timing of the load (i.e. when you know you are going to sneeze, jump, cough, lift your leg), certain muscles anticipate the impending load and contract prior to the event occurring. The joints of the lower thorax (chest), low back and pelvis, as well as the organs of the pelvis (bladder, prostate and uterus) are therefore protected against any large increases in shear forces or pressure. For the lower chest, low back and pelvis, these muscles include the:

- transversus abdominis – 3 different levels (upper, middle and lower) (deepest abdominal)

- deep fibres of multifidus – goes all the way from your sacrum to your head (deep back muscle)

- pelvic floor muscles – connect to the deepest muscles of your hips (muscles of your perineum)

- respiratory diaphragm – connects to psoas which is a deep hip flexor and spine stabilizer (breathing muscle)

These muscles must be functioning optimally for an individual to be free of low back or pelvic pain and to be continent during activities that increase the intra-abdominal pressure (sneezing, running, coughing etc.).

Continence and the urethra

Urinary incontinence is defined as the involuntary leakage of urine. Stress urinary incontinence (leakage which occurs during physical exertion) is the most common type. How common is this? The prevalence of this condition varies according to age, study design and definition. Ashton-Miller et al (2001) stated that 8.5% – 38% of women experience stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Nygaard et al (1994) noted that this condition is not limited to women bearing children and that in a study of 144 nulliparous female athletes ages 18 to 21 years, 28% suffered from SUI. Bø & Borgen (2001) found that 41% of elite female athletes experience SUI. Fantl et al (1996) stated that incontinence affects four out of ten women, about one out of ten men, and about 17% of children below the age of fifteen.

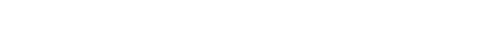

The structures that provide support for the urethra include:

- the fascia which is anchored to the inside of the pelvic bones

- the pelvic floor muscles

- the nervous system which controls the timing, endurance and strength of the muscle contraction.

If this system gives way easily, it cannot provide a backstop against which the urethra can be compressed. A useful analogy is to imagine a garden hose (urethra), with water running through it (urine), lying on a trampoline bed (the pelvic floor). Stepping on the hose will block the flow of water if the bed is very stiff and provides an equal and opposite counterforce (functional pelvic floor). If however, the bed is very flexible (i.e. loss of muscle and fascial support), the downward pressure on the hose will cause the bed to stretch and allow the hose to indent the bed. The flow of water will continue uninterrupted (DeLancey 1994). These muscles have to contract at just the right time to increase tension in the muscles and fascia if urinary leakage is to be prevented.

Optimal function requires a coordinated action of all the muscles of the of the thorax, low back and pelvis – all muscles are important. Optimally, the deep multifidus and transversus abdominis co-contract (turn on together) at different times during many functional activities and together, they assist in providing a center of support. It is also hypothesized that deep multifidus turns on when a gentle contraction of the pelvic floor is performed. In other words, when the pelvic floor muscles contract, a response should occur in the transversus abdominis (deepest abdominal) (Sapsford et al 2001) and in the deep multifidus (deepest back muscle). In dysfunction (either low back pain or urinary incontinence), this co-activation pattern is often absent or asymmetric. It has also been noted that it is wrong to assume that everyone will be able to contract the muscles of the pelvic floor through verbal commands alone (lift your vagina/testicles or squeeze the muscles around your urethra) (Bump et al 1991).

Stress urinary incontinence

Stress urinary incontinence can result when there are problems with:

- the anatomy of the pelvic floor (stretched fascia, unhealthy muscles – too long or too short)

- the motor control of the pelvic floor (absent, delayed or asymmetric contraction)

- strength and/or endurance of the pelvic floor muscles

- excessive intra-abdominal pressure for multiple different reasons that can be as far away as your cranium (head)

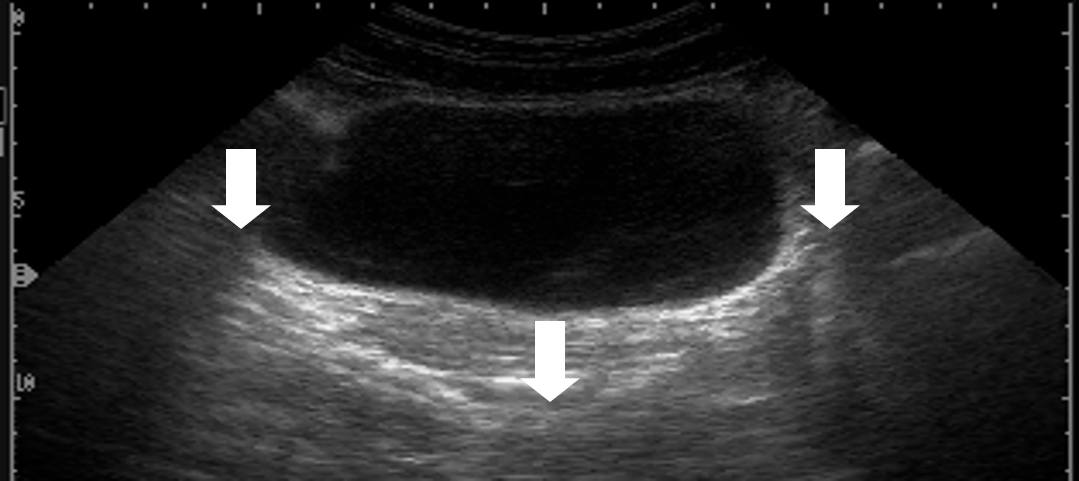

Many of these problems occur following a single major trauma (vaginal delivery of a baby or other sudden pelvic floor trauma) or, just as common, following repetitive minor trauma such as those induced with poor loading strategies or habits. When an individual uses an improper strategy to manage life loads through their thorax, low back and pelvis, particularly one that excessively increases the intra-abdominal pressure, the bladder and pelvic organs can be repetitively pushed inferiorly. This can lead to urinary incontinence if the fascial structures supporting these same organs (including the urethra) become stretched or if the pelvic floor muscles become lengthened or develop trigger points and are easily fatigued. When the bladder is observed with ultrasound imaging, it can be seen that these strategies cause the bladder to shift or move. Optimally, the bladder should move very little during low load functional tasks (e.g. lifting your leg off the table) or load through your low back or pelvis.

Since the pelvic floor muscles function as part of a team, we believe that physiotherapists/clinicians who focus on restoring function of the low back and pelvis and physiotherapists/clinicians who specialize in pelvic floor dysfunction are treating the same condition – non-optimal strategies for managing life loads, manifested either through a loss of control of the thorax, low back and pelvis (often resulting in pain), or loss of closure of the urethra (resulting in urinary incontinence). The research supports that we are merging to a common understanding of both function and dysfunction of the whole pelvis and not just its parts.

Treatment of the impaired thorax, low back and pelvis must focus on a whole body approach, one which considers the relationship between impairments in different regions of the body, and aims to restore optimal strategies for the management of life’s loads.

Stress urinary incontinence is NEVER normal, there is help, come for an assessment and we’ll show you how you can manage this condition.